Introduction to Differential Geometry

Before we start, I want to mention that this blog is largely derived from the course materials from Claudio Arezzo’s Differential Geometry course hosted by the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), and it also pulls significantly from Manfredo do Carmo’s Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces. Both of these resources are incredible for learning about Differential Geometry, and I really can’t recommend taking a look at them enough.

Section 1: Geometry of curves in $\mathbb{R}^3$

Consider $\alpha(t): [a,b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$ to be a differentiable, time-parameterized curve through $\mathbb{R}^3$. The length of such a curve is defined as

\[L(\alpha) := \int_a^b \|\alpha'(t)\|_2 \, dt.\]We say $\alpha$ is parameterized by arc-length (p.a.l.) if $|\alpha’(t)|_2 = 1$ for all $t \in [a,b]$. Now we’ll introduce some definitions to build up to a notion of curvature. Supposing $\alpha: [a,b] \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$ p.a.l., we define

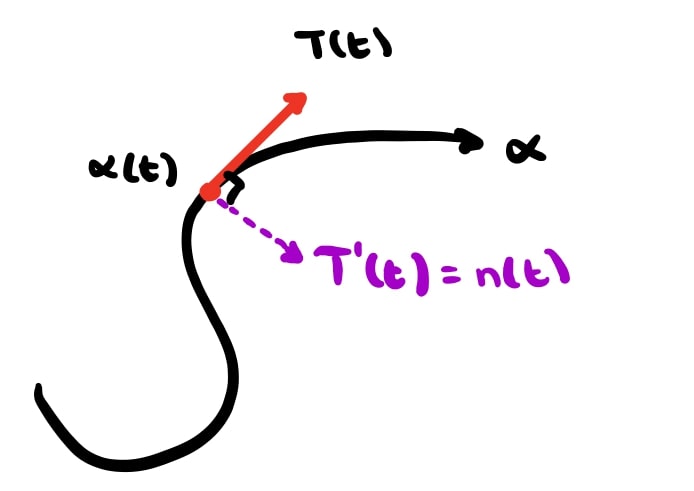

\[T(t) := \alpha'(t)\]and call it the unit tangent vector to $\alpha$ at time $t$. Intuitively, we define the curvature of the curve $\alpha$, denoted $k(t)$ to be the magnitude of the time derivative of $T(t)$,

\[k(t) := \|\alpha^{\prime\prime}(t)\|_2 = \|T'(t)\|_2.\]Put simply, the curvature tells us how quickly the unit tangent vector of our curve changes! A little more digging will give allow us to draw a clear picture of all of these quantities. Notice that, since $|T(t)|_2 = 1$, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{d}{dt} \langle T(t), T(t) \rangle &= 0 \\ \langle T'(t), T(t) \rangle + \langle T(t), T'(t) \rangle &= 0 \\ \langle T'(t), T(t) \rangle &= 0. \end{aligned}\]This tells us that $T’(t)$ is necessarily orthogonal to the unit tangent, $T(t)$. We can use this insight to further define the unit normal vector,

\[n(t) := \frac{T'(t)}{\|T'(t)\|_2} = \frac{T'(t)}{k(t)}.\]This gives us a solid basis of geometric descriptors of a given differentiable curve $\alpha$. A depiction of an example $\alpha(t)$, $T(t)$ and $n(t)$ is shown in Figure 1.

Section 2: Geometry of surfaces in $\mathbb{R}^3$

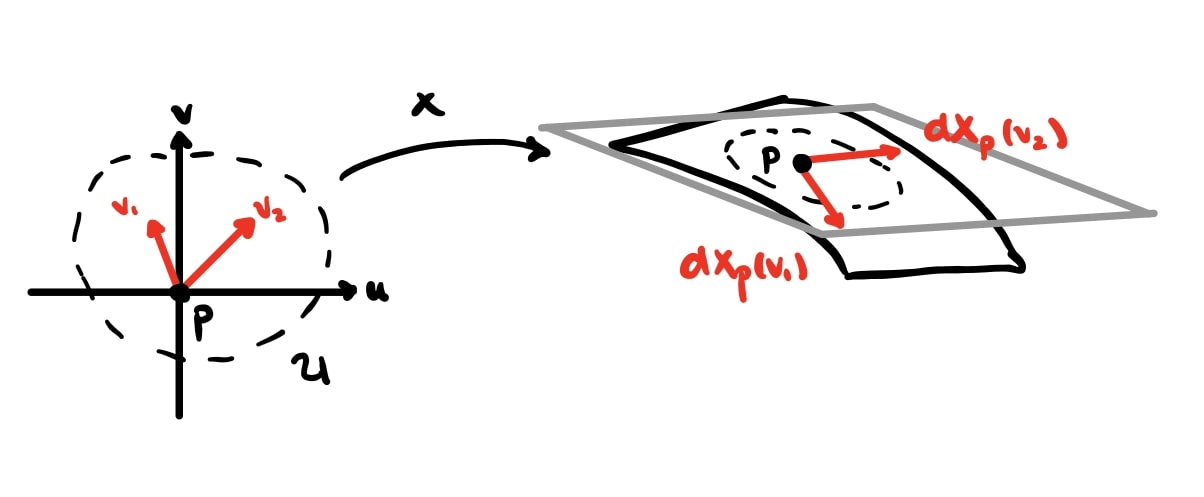

Now we can graduate to analyzing the geometry of surfaces in $\mathbb{R}^3$. Before we do so, though, we will define the differential of a map $X: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$. The differential of $X$ at $p$, denoted $dX_p: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$, is a linear map that takes tangent vectors to curves passing through $p$ to the associated tangent vector of the curve induced by $X$. Formally, let $\alpha:(-\epsilon, \epsilon) \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2$ be a curve such that $\alpha(0) = p$ and $\alpha’(0) = v$. Then,

\[dX_p(v) = \frac{d}{dt}(X \circ \alpha)\Big|_{t = 0}.\]While this definition may seem confusing, if we take a look at the matrix representation of this linear map, we see that it simply boils down to the jacobian of $X$ applied to the vector $v$,

\[dX_p(v) = J_X v.\]Remark. The function $dX_p(v)$ depends only on $p$ and $v$, not the choice of $\alpha(t) = (u(t),v(t))$.

This becomes clear when we expand the definition of the differential using the chain rule,

\[\begin{aligned} dX_p(v) &= \frac{d}{dt}(X \circ \alpha)\Big|_{t = 0} \\ &= X_u u'(t) + X_v v'(t) \Big|_{t = 0} \\ &= X_u u'(0) + X_v v'(0) \end{aligned}\]where $v = (u’(0),v’(0))$ by definition and $X_u = \frac{\partial X}{\partial u}$, $X_v = \frac{\partial X}{\partial v}$.

Now we can finally discuss surfaces in $\mathbb{R}^3$, specifically regular surfaces.

Definition. $S \subset \mathbb{R}^3$ is called a regular surface if $\forall p \in S$, $\exists$ an open subset $V$ of $\mathbb{R}^3$ such that $p \in V$ and there exists a surjective, $C^{\infty}$ map $X: U \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow V \cap S$ such that

- $X$ is a homeomorphism

- $dX_p$ is injective $\forall p \in U$.

$X$ is often called a local parameterization or a local chart of $S$. This definition establishes the notion that a regular surface $S \subset \mathbb{R}^3$ can be constructed by stitching together deformations of patches of $\mathbb{R}^2$. Then, by analyzing these deformations we’ll be able to quantify and characterize the geometry of $S$!

Tangent curves and spaces

We’ll now define the notion of a tangent space to a point, a critical geometric object in Differential Geometry. Given a regular surface $S \subset \mathbb{R}^3$, we we say $v \in \mathbb{R}^3$ is a tangent vector if there exists a curve $\alpha:(-\epsilon,\epsilon) \rightarrow S$ such that $\alpha(0) = p$ and $\alpha’(0) = v$.

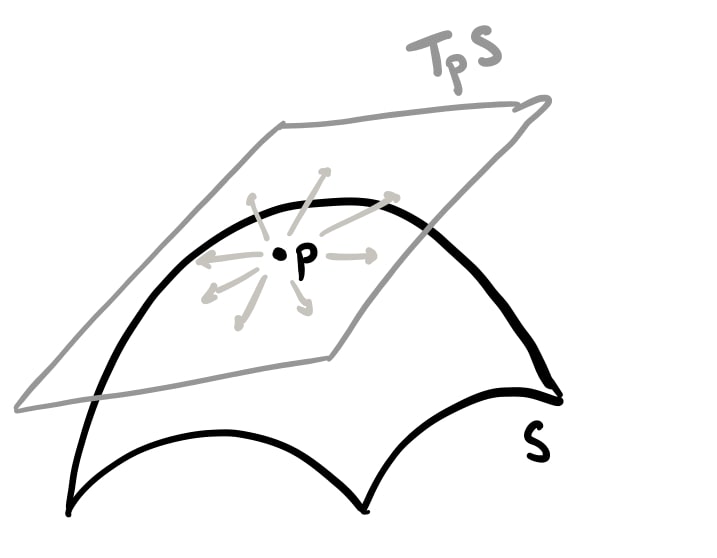

Definition. The tangent space to $S$ at $p$ is defined as

\[\begin{aligned} T_pS = \{v \in \mathbb{R}^3 \, | \, v \text{ tangential to } S \text{ at } p\}. \end{aligned}\]

Figure 2 shows an example of the tangent space to a surface. This vector space $T_pS$ actually arises directly from the charts used to construct $S$. This is illustrated in the following lemma:

Lemma. Let $X: U \rightarrow S$ be a local chart around $p$. Then $T_pS = dX_{X^{-1}(p)}(\mathbb{R}^2)$.

I’ve omitted the proof, but it arises quite simply from the definitions of the differential and the tangent space. A simple corollary of this result follows too,

Corollary. Let $X: U \rightarrow S$ be a local chart around $p$. Then $T_pS = \text{span}\{X_u, X_v\}$.

Critically, this means we have access to a basis of our tangent space about each $p \in S$ arising only from the chart $X$. Now that we’ve established a notion of tangency, we’ll do the same for normalcy.

Normal vector fields and the Gauss map

A vector field on $S$ (i.e. a differentiable map $V: S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$) is called normal if $\forall p \in S$ we have $\langle V(p), w \rangle = 0$ $\forall w \in T_pS$. Furthermore, $V$ is called unitary if $|V(p)|_2 = 1 \, \forall p$.

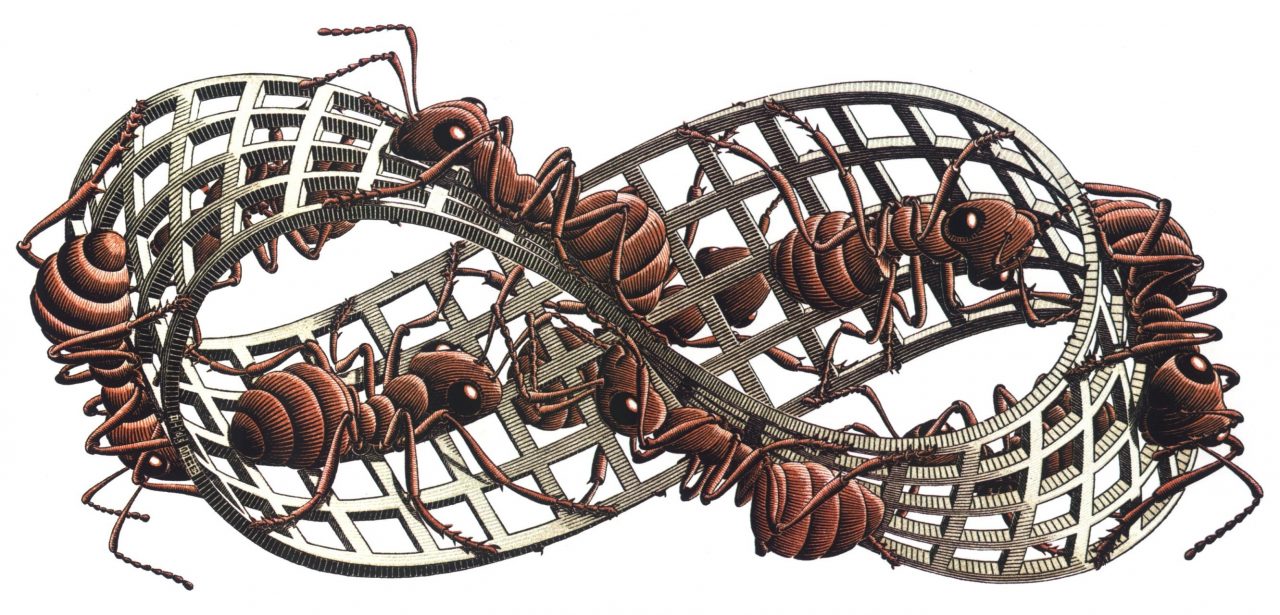

Unitary normal vector fields give rise to the notion of orientability. For example, non-orientable surfaces like the Möbius strip do not admit a global unitary normal vector field. This idea is beatifully illustrated by a painting by M.C. Escher, shown in Figure 3.

If it exists, the unitary normal vector field $N: S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$ for a surface $S$ is called the Gauss map. Studying the behavior of the Gauss map will lead to a generalization of the notion of curvature for surfaces.

The First and Second Fundamental Forms

The first fundamental form (denoted $\mathrm{I}_p$) and second fundamental form (denoted $\mathrm{II}_p$) are quadratic forms on the tangent space of surfaces - namely, they take a vector pair $(v, w) \in T_pS \times T_pS$ to a number in $\mathbb{R}$. These two maps describe describe respectively the intrinsic and extrinsic geometry of a surface $S$, and will be the subject of our study for the rest of the blog post.

Definition. Suppose we have a surface $S$ with a local chart $X: U \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow S$, and a point $p \in X(U)$. The first fundamental form of $S$ at $p$, denoted $\mathrm{I}_p: T_pS \times T_pS \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, is the map \(\begin{aligned} \mathrm{I}_p(v,w) = \langle dX_p(v), dX_p(w) \rangle \end{aligned}\) for $(v,w) \in U \times U$. It is often interpreted as the restriction of the Euclidean inner product to $T_pS$.

A visualization of the quantities used in the definition can be seen in Figure 4. For me, it is intuitive to think about the matrix representation of $\mathrm{I}_p$. Expanding the definition we see,

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{I}_p(v,w) &= \langle dX_p(v), dX_p(w) \rangle \\ &= v^T J_X^T J_X w \\ &= v^T \begin{bmatrix} E & F \\[6pt] F & G \end{bmatrix} w \end{aligned}\]where

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} E & F \\[6pt] F & G \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} \langle X_u, X_u \rangle & \langle X_u, X_v \rangle \\[6pt] \langle X_u, X_v \rangle & \langle X_v, X_v \rangle \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}\]By looking at the first fundamental form this way, we see that it tells us how much the local chart $X$ deforms the patch $U \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ along the coordinate axes $u$ and $v$ to get the patch $X(U) \subset S$! We can make this idea concrete by computing path lengths on $S,$ where we will see a clear dependence on the first fundamental form.

Let $\beta:[a,b] \rightarrow U \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ and let $\alpha = X \circ \beta$, where $X$ is a local chart for $S$. Lets compute the length of the path of $\beta$ and $\alpha$:

\[\begin{aligned} L(\beta) &= \int_a^b \|\beta'(t)\|_2 \, dt \\ L(\alpha) &= \int_a^b \|\alpha'(t)\|_2 \, dt. \end{aligned}\]We can apply the chain rule to get $\alpha’(t)$ in terms of $\beta$,

\[\begin{aligned} \alpha'(t) &= \frac{d}{dt}(X \circ \beta)(t) \\ &= X_u u'(t) + X_v v'(t). \end{aligned}\]Plugging back into the path length equation, we get

\[\begin{aligned} L(\alpha) &= \int_a^b \Big\langle X_u u'(t) + X_v v'(t), \, X_u u'(t) + X_v v'(t) \Big\rangle^{1/2} \, dt \\ L(\alpha) &= \int_a^b \Bigl(Eu'(t)^2 + 2Fu'(t)v'(t) + Gv'(t)^2 \Bigr)^{1/2} \, dt. \end{aligned}\]Rewriting $L(\beta)$ as follows,

\[\begin{aligned} L(\beta) &= \int_a^b \Bigl(u'(t)^2 + v'(t)^2 \Bigr)^{1/2} \, dt \end{aligned}\]clearly illustrates the fact that $\mathrm{I}_p$ determines the distortion of path lengths induced by the chart $X$. Now, we will move on to define and analyze the second fundamental form.

Definition. Suppose we have a surface $S$ with a local chart $X: U \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow S$, and a point $p \in X(U)$. The second fundamental form of $S$ at $p$, denoted $\mathrm{II}_p: T_pS \times T_pS \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, is the map

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{II}_p(v,w) = \langle -dN_p(v), w \rangle \end{aligned}\]for $(v,w) \in U \times U$.

Again, we can look at the matrix representation of $\mathrm{II}_p$ to get a better idea of what is going on,

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{II}_p(v,w) &= \langle -dN_p(v), w \rangle \\ &= v^T(-J_N)w \end{aligned}\]where $J_N$ is the jacobian of the Gauss map. Some calculation reveals that

\[\begin{aligned} J_N &= \begin{bmatrix} E & F \\[6pt] F & G \end{bmatrix} ^{-1} \begin{bmatrix} e & f \\[6pt] f & g \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\]where,

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} e & f \\[6pt] f & g \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} -\langle N_u, X_u \rangle & -\langle N_v, X_u \rangle \\[6pt] -\langle N_u, X_v \rangle & -\langle N_v, X_v \rangle \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}\]Again, this sheds some light on what $\mathrm{II}_p$ represents: it tells us how the normal vector changes as we move along the surface (specifically with respect to changes in the parameters $u$ and $v$ in the domain of the local chart $X$).

Theorem (Euler). For a surface $S$ suppose we have a unitary normal vector field $N: S \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^3$. Also suppose that we have $\alpha: (-\epsilon, \epsilon) \rightarrow S$ p.a.l., such that $\alpha(0) = p$, $\alpha’(0) = v$. Then

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{II}_p(v,v) = \langle \alpha^{\prime\prime}(0), N(p) \rangle. \end{aligned}\]The term on the right, $\langle \alpha^{\prime\prime}(0), N(p) \rangle$, represents the projection of the acceleration of $\alpha$ onto the surface normal. This quantity is often referred to as the normal curvature, as it represents the amount of curvature of $\alpha$ that is normal to the surface $S$ at $p$.

Proof of Euler’s Theorem:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathrm{II}_p(v,v) &= \mathrm{II}_p (\alpha'(0), \alpha'(0)) \\ &= \langle dN_p(\alpha'(0)), \alpha'(0) \rangle \\ &= \Bigl\langle \underbrace{\frac{d}{dt} N(\alpha(t)) \Big|_{t=0}}_{N'(p)}, \, \alpha'(0) \Bigr\rangle \\ &= \Bigl\langle N(p), \alpha^{\prime\prime}(0) \Bigr\rangle \end{aligned}\]where the last step follows from the fact that $N(\alpha(t)) \perp \alpha’(t)$.

Definition. The principal curvatures of a surface $S$ at $p$ are defined to be the maximum and minimum normal curvatures that an arc-length parameterized curve $\alpha$ can have, where $\alpha(0) = p$. Formally,

\[\begin{aligned} k_1(p) &= \min_{\alpha(0) = p} k_n(0) \\ k_2(p) &= \max_{\alpha(0) = p} k_n(0). \end{aligned}\]From the principal curvatures, the definitions of Gaussian and mean curvature arise:

Definition. The Gaussian curvature of a surface $S$ at $p$ is the product of the principal curvatures,

\[\begin{aligned} K(p) = k_1(p)k_2(p) \end{aligned}\]while the mean curvature is the mean of the principal curvatures,

\[\begin{aligned} H(p) = \frac{k_1(p) + k_2(p)}{2}. \end{aligned}\]For the rest of the blog we’ll focus on Gaussian curvature. While mean curvature offers a tool for the study of the extrinsic geometry of a surface, it is out of the scope of this blog post.

To give some grounding for Gaussian curvature: the plane has $K \equiv 0$, the standard 2-sphere has $K \equiv +1$, while the standard pseudosphere has $K \equiv -1$. But a key question arises: how were those quantities computed? It’s not clear how to solve the minimization problem required to compute the principal curvatures. But if we study $\mathrm{II}_p$ a little more, we’ll find that it has the ingredients to allow us to compute $k_1$ and $k_2$ directly from a local chart $X$! Recall

\[\begin{aligned} k_1(p) &= \min_{\alpha(0) = p} k_n(0) \\ &= \min_{\alpha(0) = p} \Bigl\langle N(p), \alpha^{\prime\prime}(0) \Bigr\rangle. \end{aligned}\]We can directly apply Euler’s Theorem to replace the right hand side with the second fundamental form applied to the initial velocity of $\alpha$,

\[\begin{aligned} k_1(p) &= \min_{\alpha(0) = p} \Bigl\langle N(p), \alpha^{\prime\prime}(0) \Bigr\rangle \\ &= \min_{\alpha(0) = p} \mathrm{II}_p(\alpha'(0), \alpha'(0)). \end{aligned}\]Because this last line only depends on the zero and first-order behavior of $\alpha$, we can replace it with the following,

\[\begin{aligned} k_1(p) &= \min_{\|v\|_2 = 1} \mathrm{II}_p(v, v) \\ &= \min_{\|v\|_2 = 1} v^T(-J_N)v. \end{aligned}\]The interpretations of the eigenvalues of a quadratic form as the minimal and maximal values of the quadratic form restricted to the unit sphere tells us that the eigenvalues $\lambda_1$, $\lambda_2$ of $-J_N$ are the principal curvatures:

\[\begin{aligned} k_1(p) &= \lambda_1 \\ k_2(p) &= \lambda_2. \end{aligned}\]This gives rise to new equations for the Gaussian and mean curvatures:

\[\begin{aligned} K(p) &= \det(-J_N) = \frac{eg - f^2}{EG - F^2} \\ H(p) &= \frac{1}{2} \mathrm{Tr}(-J_N) = \frac{1}{2}\frac{eG + gE - 2fF}{EG - F^2}. \end{aligned}\]Section 3: Gauss’ Theorema Egregium

In this section we’ll walk through Gauss’ Theorema Egregium, one of the major results of differential geometry. To do so, we first need to establish the definition of isometric maps and some properties of them.

Definition. Surfaces $S$, $\tilde{S} \subset \mathbb{R}^3$ are called isometric if there exists a diffeomorphism (a $C^1$ map with a $C^1$ inverse) $f: S \rightarrow \tilde{S}$ that takes each curve on $S$ to a curve of the same length on $\tilde{S}$.

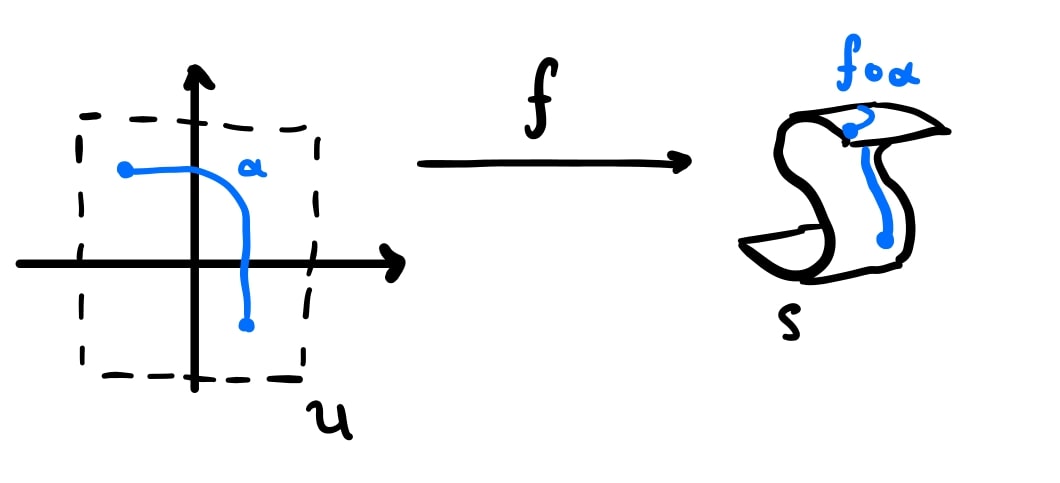

An example of an isometric surface pair, the plane and the S-surface, is shown in Figure 5. These surfaces are isometric because we can bend, but not stretch, the plane so that it coincides with the S-surface. Such a transformation does not distort the length of paths!

Theorem. Patches of surfaces $S$, $\tilde{S} \subset \mathbb{R}^3$ are isometric if there exist charts $X: U \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow S$ and $\tilde{X}: U \subset \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \tilde{S}$ such that the first fundamental form $\mathrm{I}_p$ coincides.

Proof sketch: An isometric map between patches of $S$ and $\tilde{S}$ preserves path lengths. We also have shown that the distortion of such path lengths incurred by the charts $X$ and $\tilde{X}$ is determined completely by their respective first fundamental forms. From here, it’s not hard to show that since an isometry exists (and path lengths are therefore preserved under this map) the first fundamental forms of the two surfaces must coincide.

Now we are in a position where we can state Gauss’ Theorema Egregium.

Theorem (Gauss). The Gaussian curvature of a surface $S$ is invariant under isometries. That is, if $f: S \rightarrow S’$ is an isometry, then $K(p) = K(f(p))$ $\forall p \in S$.

Proof sketch. One can show that the Gaussian curvature $K$ depends only on the zero and first order behavior of the first fundamental form $E$, $F$ and $G$. Thus, $K$ can be written as

\[\begin{aligned} K &= \frac{eg - f^2}{EG - F^2} \\ &= \frac{\phi(E, G, F, E_u, E_v, G_u, G_v, F_u, F_v)}{EG - F^2} \end{aligned}\]where $\phi$ is some messy function of the first fundamental form and its partial derivatives w.r.t. $u$ and $v$. Since $K$ can be written as a function of only the first fundamental form, and by the previous theorem isometries preserve the first fundamental form, we can conclude that the Gaussian curvature $K$ must be preserved under isometries!

Implications

Gauss’ Theorema Egregium is a major result of differential geometry, as it sheds light on the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic curvature. Take, for example, an open subset of the plane and roll it into a cylinder. Intuitively (and one can check this by computing $E,F,G$) the lengths of paths are completely unchanged. Since $K \equiv 0$ for the plane, Gauss’ Theorema Egregium tells us that this must mean $K \equiv 0$ for the cylinder!

This arises from the fact that Gaussian curvature measures the intrinsic distortion of a surface from a Euclidean space. Rolling the plane up into a cylinder introduces extrinsic curvature, but does not stretch or warp the surface in any way. One can see this by playing around with a piece of printer paper. Anything you do to bend or fold the surface that does not introduce any tears or pleats is introducing extrinsic curvature (and assuming no hard creases are made, such a transformation is an isometry)!

Another huge implication of the Theorema Egregium is in the field of Cartography. Since $K \equiv 0$ for the plane and $K \equiv +1$ for the sphere, the surfaces must not be isometric. Therefore, one cannot create a distance-preserving projection of the sphere onto the plane.